Single-origin coffee beans that don?t get traded for commodity prices. It?s a piece of contemporary history that grains all over the world read about with awe and a sting of envy. If they could read, that is. In the grand scheme of things, grains and coffee beans have some equally daunting challenges ahead. To understand these challenges, we talked to two quality and transparency-focused coffee roasters whose love for coffee is inseparable from their respect for the coffee farmer.

Estimated reading time: 23 minutes

– A couple of years ago, McDonald?s in Denmark launched their McCaf? concept. They promoted this with a campaign that said something like ?finally fair coffee prices?.? Their idea was that coffee was way too expensive in Denmark, so they gave out free coffee for the whole month, says Peter Dupont, CEO of Coffee Collective, and continues:

? This provoked us because if one wants to have a conversation about fair coffee prices, then one needs to talk about what the farmers get paid. How much did McDonald?s pay the farmers so they could give coffee away for free?

The impossibility of this equation made Coffee Collective respond to McDonald?s campaign through a couple of letters to the editor at Politiken, the New York Times of Denmark. In this correspondence, Coffee Collective did give McDonald?s a point for stating that not all caf?s that charge 40 DKK for a cup of coffee are worth 40 DKK taste-wise.

– The point is that a much lower price than this would force the farmer to operate at a loss, says Peter Dupont.

For Coffee Collective, paying a reasonable price to the farmers is about ignoring the New York Stock Exchange?s C-price index, where the commodity price for coffee gets set. Instead, they trade directly with the coffee producers and reward them with quality bonuses that sometimes render as much as 400 percent above the C-price. To Peter Dupont, this is not just about common decency and fairness. It is intrinsically linked to ensuring a supply of higher quality beans, increased biodiversity, and more sustainable farming practices.

?We Let Them Decide The Price?

Like Peter Dupont, Anne Lunell does not dodge the subject of price. Paying the coffee farmers well for their work is a core principle for her.

– We never negotiate price. We simply pay them the price they ask for. Which is the price they need to take in order to grow coffee in a financially, ethically and environmentally sustainable way, she says.

Anne Lunell is a co-founder of Koppi, a Swedish quality roaster. Hence, the farmers Koppi source their coffee beans from also get compensated according to their products? quality?and not according to an abstract commodity index far away. She speaks warmly of the producers Koppi has chosen to have long-term partnerships with. They visit them at least once per year, and spend considerable time with the families during their stay. Not just because it?s enjoyable to have coffee and enjoy meals together, she says, but also to get first hand updates on their farming practices and changes that have been implemented since the last visit.

– If we want the best coffee, we need dedicated and skilled producers who are allowed to and can afford to cultivate quality produce. This requires knowledge, time, dedication and very hard work; as buyers and roasters, we must not only understand that but also enable it in every way we can, she says.

– And it starts with paying well.

So, why are there unreasonable prices on the market in the first place?

When one drops mega concepts like commodity price, biodiversity, and climate change, people start losing focus. This is understandable; although one grasps the notions, they are daunting. And when you put them in close proximity to each other, it renders the kind of feeling you would get if you knew you had to take your final exams for the semester tomorrow morning, but you only just got the books today. And to be honest, the threats to our environment and long-term survival are monumental. There is no way around the magnitude of the challenges, nor the feeling of unease that comes from knowing that much is directly linked to what we eat and drink and how it is produced, sold, and paid for.

But there is also hope.

So let?s take a closer look at the notion of commodity and commodity price. Why do coffee roasters like Coffee Collective and Koppi turn their backs on it? And how are they linked to other pressing matters like climate change?

PROFIT OVER PEOPLE

Let?s cut to the chase and add one more mega concept to the list?colonialism. The global coffee trade was built on a system established to chase low-cost labor. The colonial trading system took advantage of nearly free land and nearly free labor to deliver a nearly free product to people who could commercialize it. This is not only a brief description of the history of the coffee trade or the coffee industry but also cocoa and dozens of other tropical commodities. Not that there is something inherently wrong about wanting to get a good ?bargain?. The incentives that drive trade are logical. It is also fair to remark that the history of global trade is a complicated web of merchants, trading houses, and commodity exchanges. Not everything about economic globalization in the 19th and 20th centuries needs to be understood through the lens of imperial politics. Conducting economic transactions in a multicultural business world is, well, multifaceted. However both aspects are true in this (hi)story: As the complex 19th century trade web brought exotic riches to a hungry world?it did so underpinned by ruthlessness. The roots of the global commodity trade are traced back to the first slave-run sugar plantations of the Portuguese-controlled Madeira in the 15th century and the Dutch slave colonies of the 17th century.

While the callous disregard for human life tainted the European merchants who built riches with the help of cheap and often involuntary labor from colonies, the most interesting factor in this equation is the birth of a constant: scale.

Global trade meant global reach. The amount of farm produce traded for money became massive, and encouraged standardized efficiency, and cemented food as a bland commodity. A product that could be traded just like any other non-life sustaining product for whatever price the market deemed suitable.

ANONYMITY MADE YOUR COFFE

As scale contributed to anonymizing the farmer, so did distance. The supply chain became long, geographically, and in terms of how many intermediaries distributed and redistributed the produce.

When you consider the journey a commodity, like coffee, took and still takes, from farm to cup, you realize that commodification of farm produce is a process. A lengthy process that involves farm inputs, actual farming, purchasing and processing, wholesaling, and retailing. Farming and the farmer?or the peasant or the slave in the colonial system?is reduced to a component in an extensive system of agribusiness. A primary producer that is seldom compensated fairly.

Hence, the word commodity remains tainted.

NEXT LEVEL ANONYMITY

The scale and distance of the trade anonymized the primary producer. Today these aspects have warped into abstract commodity exchanges where coffee is subjected to, for example, speculative price movements. Speculators make complex bets on the price changes with advanced financial instruments. Making the distance between farm and (coffee) cup seem even longer and more unclear.

– 15 times more coffee than what is actually produced gets traded on the stock exchange. This is speculation, Peter Dupont states and agrees that it is a sort of gambling.

– On an ideal market, supply and demand govern the price, but on the commodity market for coffee, the actual physical supply and demand are not reflected in the price set on the stock exchange. The price is determined by commodity traders that interpret signals of expected harvest outcomes. This accelerates the exchange of coffee before there is any actual coffee, he says.

While the speculation dilutes the coffee price, Peter Dupont is quick to underline that even without the speculation layer, the coffee index does not reflect reasonable market-equilibrium prices for coffee. Partly because the quality standards are simple, making it pretty easy for most green beans to enter the commodity market. A commodity market streamlines the produce per definition. It is not a vivid bazaar where a multitude of buyers meets a multitude of sellers. It is a vast, standardized, and instrumental one-size-fits-all matrix.

Isn?t that just supply and demand?

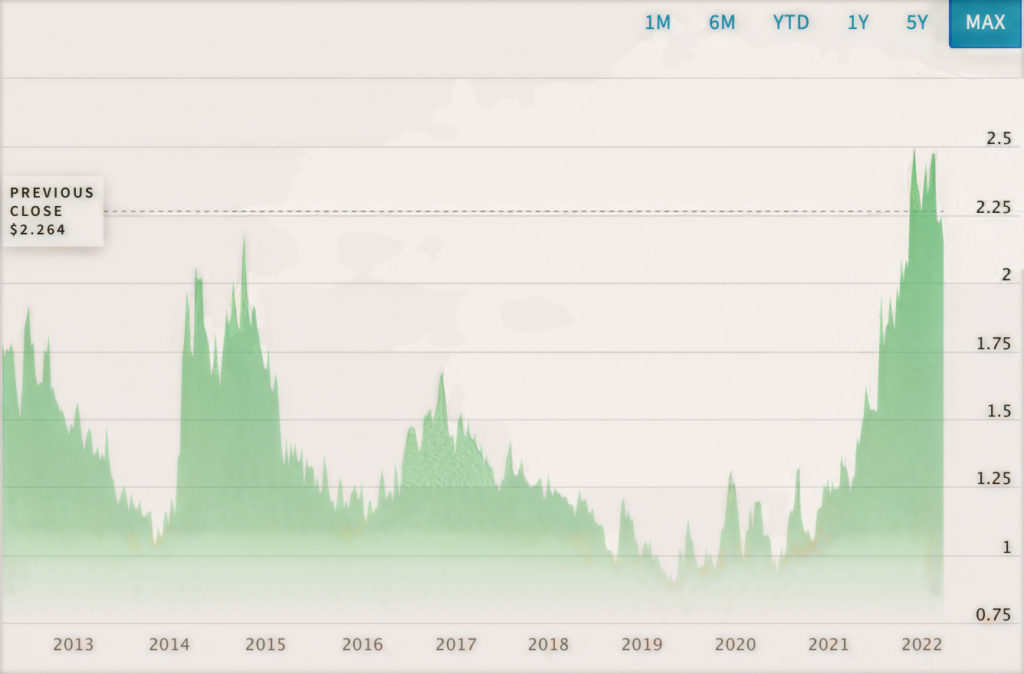

Over the last twenty years, the price index for coffee has gone up and down in big waves. And when the price hits a low, there is a crisis for the suppliers, as in 2019 when the New York Stock Exchange coffee price fell below 1 USD per pound. But how is that a crisis, one might ask? Isn?t this just the market?s cyclical supply and demand movement? When there is a lot of coffee on the market, the prices go down, and vice versa, even though it is diluted by speculation.

It is a crisis for the millions of anonymous coffee farmers who can not cover their production costs. Also, note that the index prices have no adjustment for inflation. What. So. Ever.Well, shouldn?t the smaller farmers leave the market by selling off their land, the devil?s advocate would ask. That?s what the market forces are ?for?, right?

The market forces are having an effect on the coffee market, foremost by huge consolidation processes on ?the top?. This is what that looks like:

- More than 80% of global coffee sales are attributed to three multinational corporations.

- Coffee is grown in more than 70 countries, but nearly 70% of the world?s coffee is produced by just four countries: Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, and Indonesia. While the coffee industry is a production machinery at scale, coffee cultivation is still mostly small-scale production. So here?s a third set of numbers to meditate on:

- 25 million smallholder farmers produce 80% of the world?s coffee, according to, amongst others, Fairtrade International.

The market forces have not been able to create more large scale coffee-farmers by fighting price to a draw. Instead, the three points indicate a few-against-many-situation. A handful of term-setting multinational companies on the buying side, with many disparate primary producers on the selling side.

Market forces can be a driving force for good because they drive efficiency. Industrialization, to add one more fairly big concept to this story, has driven up efficiency in farming and food production. But growing and producing food is not the same as building cars or assembling toys.

Industrial methods are not equally applicable to all farming production?and can?t be pushed to the extreme without generating ecological and ethical harm. This becomes evident in the coffee business.

COFFEE FARMING IS NOT LIKE FARMING GRAINS

– Coffee cultivation, harvesting, and processing are much more labor-intensive processes than grain production. Primarily, Anne Lunell says, because it takes time for a coffee tree to ?start bearing fruit. Between 3-4 years generally?.

– And when the tree starts producing cherries, they do not ripen all at once – not even on the same tree. So each tree has coffee beans that go from green to half ripe to perfectly ripe and over ripe. There can also be flowers which means that additional fruits are on their way. So you can not go to one tree and pick all the cherries at once. The farmer needs to return to each tree several times during a harvest period so only the perfectly ripe cherries get picked. Trees that grow on steep mountain slopes. And after this, of course, is all that hard work that goes into sorting, washing, fermenting, drying, turning and then sorting the coffee beans.

– There are, however, exceptions to this, like brute picking techniques or machines, but then all the cherries are combed off regardless of maturity, which affects the quality of the final product, Anne Lunell explains.

In general, the market forces have not been able to push farmers to consolidate and move on to other professions en masse. Instead, the entire (regular/commodity) coffee market depends on farmers willing to draw the shorter straw in everydown-cycle. The actual cost is paid by the farmers and their land and environment.

Hence, while the global coffee trade system came of age chasing free labor, it is fair to state that it is still taking advantage of nearly free land and nearly free labor to deliver a nearly free product to big corporations that know how to commercialize it. Three giant corporations, to be specific, and to repeat ourselves.

?NEOCOLONIALISM?

As stated earlier, three players dominate the coffee market. This means that there is a sole supplier scenario rising on the horizon like The Dark Tower on Middle-earth. This is, well, scary. Because how do the big consolidated players of the conventional coffee industry leverage their size?

Thus far, they show examples of Saruman-style relation-building, where they ask for 180 days, or a year, in payment extensions. Which is an awfully long time to wait for money when you are a coffee farmer. Especially when the price is below your production costs.

THE ANTIDOTE?WHAT IS THE CURE?

As in the Lord of the Rings, concerned readers can find some solace in knowing that there are other forces at play in our story too. As there have always been.

In a widely circulated pamphlet from 1791, the writer William Fox wrote, ?.. if we purchase the commodity, we participate in the crime?.

He echoed the British abolitionists who opposed the suffering behind sugar grown and processed by African slave labor in what was then the West Indies. Led by the Quakers, the protests constructively gave rise to a Free Produce movement that spread to America and influenced merchants to use ?not derived from chattel slavery?

“As long as farmers are paid a meager price, we can not expect them to invest in regenerative practices and other long-term strategies that increase the odds for coffee still being around in the future.”

Peter Dupont, CEO at Coffee Collective

The Free Produce movement has an analog in today?s Fair Trade certifications, which was sparked in the early 1990s by the appeals from small-scale coffee farmers in Mexico.

– However, the Fairtrade certificate is not a viable solution, according to both Koppi and Coffee Collective.

– Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance and other certificates are excellent standards. It?s nice to read about it at the store, but in reality, they are squeezing the farmers even more. Because they add about 50 pages of extra work and reward the farmer with a minimal price increase of around 5-10%, says Peter Dupont.

He also thinks the European organic label is questionable, even though half of their coffee is certified organic.

– We make sure the coffee producer gets compensated for the extra work of becoming certified organic. Still, the situation becomes bizarre when some farmers are more than organic beforehand. Since they can?t afford to buy pesticides in the first place.

Peter Dupont says that the nice certifications are catering to the big suppliers? needs rather than the farmers.

– Rainforest Alliance accepts that the buyer is given up to a year?s credit.

– We expect all our farmers to follow environmental legislation and other national and international legal requirements, like IOL rules. But as importers and roasters, we don?t have the right to tell them how they should farm. That is to be colonial; it is to repeat history; it is us coming down there to make money and excusing ourselves with the preconception that we need ?to develop the savages?. We want to get as far away from this notion as possible.

– And things are never going to be sustainable unless it is locally embedded. The top-down approach does not work. Especially not if the farmers don?t get paid appropriately. – When I studied for my master?s [in International Development and Ecology] I went to Matagalpa in Nicaragua. I knew there was an issue with coffee production polluting the water streams with organic material. That was the theme I wanted to study. But when I got the angle approved from the university and went there, I learned that it was already illegal to pollute the water.

That was a wake-up call for Peter.

– I realized that in many of these countries, there are suitable legislations in place, but the implementation is lacking and/or hindered.

The only way to get at that is to pay the farmers accordingly. Then the rest will follow, is Peter Dupont?s sentiment and experience. And there is no time to spare because environmental concerns are pressing coffee crops everywhere.

– For the last 10 years, we have seen the rain balance changing. There is usually a dry season and a rainy season. The rain season ignites the crop cycle. But when it rains all the year round, the cycle gets restarted several times. So climate change is messing up the coffee cycle. We also see an increase in fungus diseases like leaf rust.

– In the short term, it is mainly extra stress for the farmers that need to work harder for the same price.

TRANSPARENCY Every coffee bag from Coffee Collective displays how big the quality bonus is. On this variety from Yemen, the quality bonus is 443% above the market price. When buying the coffee online, or at the shop, the consumer can see additional data on the price of each coffee variety, per pound (lb): 1. The Producer Price, in USD/lb 2. World Market Price, in USD/lb 3. Return to Origin, in USD/lb FOB (Free on Board Price). How many years the relationship has endured between the roaster and the farmer. All coffees are directly traded except this one, which comes through warfair.org, a company that only trades with producers in conflict-affected countries. Besides being a B-corp, Coffee Collective has also signed the Transparency Pledge with a number of coffee roasters in the world

So a high price makes it possible for farmers to implement more sustainable farming practices?

– I see it the other way around. As long as farmers are paid a meager price, we can not expect them to invest in regenerative practices and other long-term strategies that increase the odds for coffee still being around in the future.

– Organic and other certifications are not creating enough incentives for this.

– Instead, we believe in having a soft approach where we work together with our farmers on different projects.

Peter Dupont explains how they have an ongoing project called ?Our Plot? in Brazil, initiated by the coffee producer Daterra. They approached Coffee Collective in 2014 with the idea to test how coffee trees could be as self-sufficient as possible within an ecosystem. To do this, they have, in Brazil, placed nitrogen-fixing shade trees, called Inga, in order to minimize the need for fertilizers. They have also applied compost around the coffee trees to avoid the need for unnecessary pesticides. Additionally, the Inga trees provide shades that help the plant retain water. The shade slows down the ripening of coffee cherries, which ensures an uneven maturation that in turn increases the flavor complexity in the cup. Interestingly enough, the project is also studying if older coffee varieties from before the 1950s would perform better in the ?Our Plot?-ecosystem. They suspect that these might be better suited for growing without chemicals than newer varieties.

Today 60% of all coffee species are threatened with extinction. The big Coffee Arabica species is especially vulnerable to climate change since it is less adaptable. Wild coffee species, of which there are around 124, are deemed critical for coffee crop development today. Because they are more tolerant of high temperatures and drought.

As with grain farming, growing more species and varieties within these species is deemed crucial for long-term supply.

?We Used to Call it Direct Trade.?

Coffee Collective was founded on the belief that it is possible to work around the described colonial commodity structures of the world coffee market. And that it is necessary to do so. Hence they, just as Koppi Coffee Roasters, cultivate direct relationships with the farmers they like. Even though the commercial relationship differs a bit depending on which country they are in.

– Our biggest, in terms of how much farmland they have, is in Brazil. They are a full-scale producer that does the important post-harvest treatment as well as the export themselves. And on the opposite end of the scale, we have a cooperative producer in Kenya. The cooperative does the post-harvest treatment but buys the green beans from their members, which are 1000 small-scale farmers, Peter Dupont says.

– In Kenya, we do not know each of the farmers personally, but we do go out to the countryside to see and learn, which is still a deeper level of engagement than what the Fair Trade organization does. They only work on the export level.

When Coffee Collective negotiates the price with their producers, the situation differs on the same spectrum.

– On one end, there?s the Brazilian producers who do not negotiate; they send us a significant quality index sheet for each harvest with the price. In Kenya, the situation is the opposite. The coffee here is undervalued because the quality is so high. This year we paid 6,5 USD per pound, we raised it from 6 USD per pound. [The C-price is a bit over 2 USD per pound at the moment. Editor?s note.]

– Colombia is somewhere between Kenya and Brazil. We can go back and forth a little bit when we discuss the price with the Colombian farmers.

– We used to call what we do ?direct trade?. But the word we like to use to describe our business model is transparency.

COFFEE THAT DOES NOT NEED MILK

In many ways, both Coffee Collective and Koppi are proof that a different market is possible if you do something about it?heroes that give the Sarumans of this world a run for their money. They are no anomalies either. These roasters are actors on the specialty coffee market which, at large, have an anti-commodity approach, as described in this story. Not all of them are as focused on transparency and fair pay as on the in-cup experience, but they all recognize the link between high-quality coffee supply and higher price tags on the green beans.

The term ?specialty coffee? is credited to the Norwegian Erna Knutsen, who is said to have coined the term in 1974, during a pivotal experience when an Indonesian man stopped by her office with a bag of Mandehling Sumatra. Specialty coffee or high-end coffee later became known as the best coffee in the world, and other key figures of Erna Knutsen?s calibre, like George Howell, drove this market forward.

This movement has evolved to what sometimes is referred to as Third Wave Coffee. A term coined by Trish Rothgeb, who found the quality focus some caf?s and baristas had in Norway exceptional. Rothgeb is a barista veteran from the Bay Area in California, USA, who came to Oslo to work in 2002.

It was also in Oslo where Anne and her partner, Charles Nystrand, indulged their careers as baristas before they moved back to Sweden and founded Koppi. As did Peter Dupont in 1998.

Both Anne and Charles are former Swedish Barista champions with an international following. People from all over the world come to visit their roastery in Helsingborg in the South of Sweden, which Anne describes as a humbling experience.

Today Koppi, and Coffee Collective, are two of the most important front runners in the specialty coffee movement, or the Third Wave Coffee movement?a concept that has come to entail more than ?just? the perfect in-cup experience which Trish Rothgeb initially referred to when she came to Norway. A segment with a solid growth trajectory since the late 80s, increasing its market share country by country, cup by cup.

But when we ask Coffee Collective about their specific success and how long it took for them to ?make it,? Peter Dupont disagrees with the premises of the question.

– I do not think we have made it. My ambitions are more in making the coffee market better, he says and points out that at this very moment, the commodity price for coffee is 2 USD per pound.

– That is an improvement from the 1 USD per pound we had not long ago. But it is just fluctuations, he says and points us back to the bigger picture.

– We do not talk to our farmers about commodity prices when the price is negotiated.

THE REASONABLE PRICE

Coffee Collective, and Koppi, are value-driven change agents, balancing craft and ethical pricing in a consumer market spoiled with commodity prices but starved on rich taste profiles. They are successful within the quality coffee segment. But can this discrepancy between what the average coffee drinker and the average coffee farmer thinks is a ?reasonable price? ever be bridged? The McCaf? campaign gives a discouraging answer to that question.

– When we charge 100 DKK for 250 grams of coffee, some people get offended because they can get more than a kilo for 100 DKK or less at the supermarket, Peter Dupont says.

But he does not believe in going back to the regulated world-market situation of the 60s – 80s when governments had more control over imports and exports.

– That is not realistic. But I do believe that change within the market economy is possible.

To change people?s value perception of coffee, we have to show what a better functioning market economy looks like.

According to Peter Dupont the key variable for this is transparency.

– Transparency for us is who produced it, but also financial transparency.

All Coffee Collective coffee bags state which farm, and farmer the coffee came from, but also how much they were paid. All their coffee is labeled with information which makes it easy for anyone who wants to check the accuracy of each statement.

When the consumer buys your coffee or buys into the concept, is it taste or fairness that drives them?

– I can not choose. We underline both. Quality is, however, very important because the customer would not return otherwise, even if they thought the price was fair. At the same time, the consumer that loves the taste needs to know why a higher price matters.

When a Value-Driven Coffee Roaster is Allowed to Dream

When asked about the most optimistic scenario for the global coffee market Peter Dupont brings our attention back to the black tower scenario?where the market seems to be heading towards a sole supplier situation: More than 80% of global coffee sales are attributed to just three multinational corporations, which is just not sound. To get rid of these ?knots?, he explains, would be key. Thus, when gazing into the future through his most optimistic binoculars, Peter Dupont sees a coffee market where millions of coffee farmers reach millions of different quality coffee roasters on millions of coffee markets all over the world. It is a more-is-more scenario where we move from a centralized non-transparent top-down model to a distributed network model. It?s a scenario where global trade becomes local trade, creating that bazaar where a multitude of buyers meets a multitude of sellers on local markets everywhere.

– Keep in mind, Peter Dupont notes, that the shipping of coffee beans from one continent to another only makes up for five percent of its total supply chain emissions.

Peter Dupont?s many-to-many-market could be the antidote to the current state of affairs. It would then coincide with the teachings of the late Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom.

Can the Current State of the Coffee Market be Called a Tragedy of the Commons?

Elinor Ostrom proved that there need not be any ?tragedy of the commons? if those who govern their resources are allowed to self-organize. Her work was about communal ownership. For our story it is her notion of trust in the humans closest to the resources that is key. Elinor Ostrom observed that communities can sustainably manage shared resources if there is no central planning. She advocated dispersed decision centers, rather than a top-down hierarchy because local actors possess information a central planning group cannot: Be they government officials or humungous coffee corporations with certifications.

So, where does all this leave us?

Perhaps it leaves us with a question and an uplifting answer.

What happens if we throw the ring of commodity-pricing in the fires of Mount Doom?

We get diversity.